"None

of them knew the colour of the sky"

"None

of them knew the colour of the sky" "None

of them knew the colour of the sky"

"None

of them knew the colour of the sky"

by Hubert Beck

"None of them knew the colour of the sky. Their eyes glanced level, and were fastened upon the waves that swept towards them. These waves were of the hue of slate, save for the tops, which were of foaming white, and all of the men knew the colours of the sea."

These are the first three sentences from the story, The Open Boat (1898) by Stephen Crane with the subtitle: A tale Intended to be After the Fact: Being the Experience of Four Men from the Sunk Steamer Commodore.

For almost a quarter of a century, Dutch artist Wil Wiegant has been on a voyage searching for significant images. This catalogue charts his progress and development with examples of his work and is an opportunity for him to weigh - up his journey so far. Like the solo mariner, Wil Wiegant understands the loneliness of the artistic process. He does not belong to any particular school and does not follow fast-changing trends but allows himself, in his own persistent way, the luxurious use of time and a well honed perseverance to paddle his own canoe.

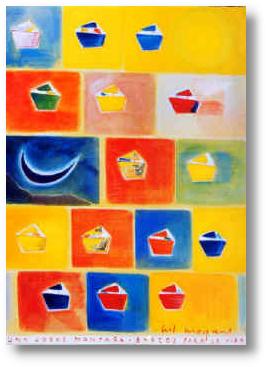

As for many artists of his generation, (Wiegant was born in 1951) the international developments in art between the fifties and seventies had a decisive impact on him. One can recognize in his earlier works a dialogue with American Abstract Expressionism and the influence, for example, of painters like Jackson Pollock. Likewise, one can recognize in his serial ordering of the subject, in his use of signs, and in the flatness of his pictorial space along with his extensive use of primary colours - red, yellow and blue - the basic elements of Pop Art. What is remarkable is that one is not played off against the other. The "realistic" use of products and brands from the consumer-world, found in Pop Art, are absent from Wiegant's paintings. What one can see in Wiegant's work - as with Pop Art's most well known representative, Andy Warhol - is that the colourful and decorative elements and the serial ornamentation have a double meaning where the surface plays a decisive role. Everything is on the surface - this is what is really telling. For Warhol, there is nothing beneath the surface.

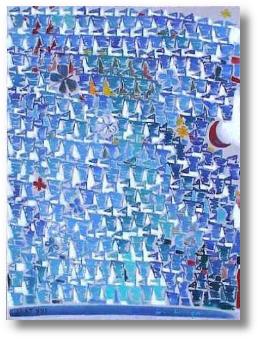

The central motif in Wiegant's painting is the boat. His ordering of the figure/ground variations in his Boat paintings with their grid-like patterns, ensures the 'boat' functions, in the first place as a sign and not as a symbol. Already, John Cage, the American artist/composer, who had a great influence on the arts of the sixties and thereafter, had postulated that an object is a fact and not a symbol. Wiegant admires Cage's work enormously and has dedicated a series of drawings to him of which one is reproduced here. In a similar fashion, the ground - forms in other works by Wiegant are without any concrete motif. On the other hand, these paintings have a romantic sub-text - the motifs are highly metaphorical signs. One can discern a yellow storm in Wiegant's paintings, reminiscences of the drama in the painting, The Raft of Medusa (1819) by French Romantic painter, Theodore Gericault (also "intended to be after the fact").

"The little boat lifted by each towering sea and splashed viciously by the crests, made progress that, in the absence of seaweed was not apparent to those in her. She seemed just a wee thing, wallowing miraculously top up, at the mercy of five oceans. Occasionally a great spread of water, like white flames, swarmed into her."

Yet

Wiegant's paintings are not about the pathos of Gericault's 'human pyramid' -

although the sails of his boats do interestingly allude to the triangular mass

of human misery depicted by Gericault - to be sure, Wiegant is not concerned at

all about the human image; his paintings are definitely not intended to be after

the fact! Gericault's paintings are also not about 'the facts' but about

symbolically representing human hopes and aspirations in social and political

life. This new discourse that surrounded early 19th century Romantic painting is

also evident in Crane's writing about the suffering of the common man. Even for

the naturalist Crane, the shipwreck has a metaphoric meaning, and his story 'The

Open Boat' can be read as an existential parable. Crane's characters don't

create their world, things simply happen to them, their circumstances seem to be

without meaning but always their circumstances have the last say. Interpreted

thus, Crane is a modern writer - a classic modernist. Wiegant's paintings seem,

at first glance to be miles apart from Crane's position. But in spite of (or

maybe because of) the reduction of abstract forms and signs and especially the

repeating of motifs - again and again the moon and sun (see, for instance,

Barcos Luna y Sol) - and in spite of an aestheticism which reminds us of the

water, light and sky found in French Impressionism, there is clearly a content

brought into play from pre-modernity that is still powerfully symbolic.

Yet

Wiegant's paintings are not about the pathos of Gericault's 'human pyramid' -

although the sails of his boats do interestingly allude to the triangular mass

of human misery depicted by Gericault - to be sure, Wiegant is not concerned at

all about the human image; his paintings are definitely not intended to be after

the fact! Gericault's paintings are also not about 'the facts' but about

symbolically representing human hopes and aspirations in social and political

life. This new discourse that surrounded early 19th century Romantic painting is

also evident in Crane's writing about the suffering of the common man. Even for

the naturalist Crane, the shipwreck has a metaphoric meaning, and his story 'The

Open Boat' can be read as an existential parable. Crane's characters don't

create their world, things simply happen to them, their circumstances seem to be

without meaning but always their circumstances have the last say. Interpreted

thus, Crane is a modern writer - a classic modernist. Wiegant's paintings seem,

at first glance to be miles apart from Crane's position. But in spite of (or

maybe because of) the reduction of abstract forms and signs and especially the

repeating of motifs - again and again the moon and sun (see, for instance,

Barcos Luna y Sol) - and in spite of an aestheticism which reminds us of the

water, light and sky found in French Impressionism, there is clearly a content

brought into play from pre-modernity that is still powerfully symbolic.

Ships and boats carry the sun and the moon over the seas; and the earth is a boat that floats on ancient waters. As bearers for the sun and moon, ships evoke the creative power and fertility of water. And of course, they also stand for adventure and the urge to explore and discover. They symbolise the voyage across the sea of life and also across the waters of death. The ship of life that sails away over the waters of creation is an axial symbol - the mast is the 'axis mundi' and also, in general, the cross represents 'the tree of life'. In Christian tradition, the Church is the Ark, the vessel of deliverance and sanctity against temptation.

"It would be difficult to describe the subtle brotherhood of men that was here established on the seas".

The cross is the mast of the boat. The rowers are the Apostles.

"The correspondent wondered ingenuously how in the name of all that was sane could there be people who thought it amusing to row a boat".

In Buddhism, 'the boat of learning' makes it possible to cross the ocean of existence and transformation to reach the shore of Nirvana.

A breaking point in Wiegant's work, opposed to the seemingly playful, decorative nature of his boat paintings, and evocative of a 'quasi' shipwreck experience - comes from his black and white photographs. Birma Road is a photographic image worked on with yellow ink and bandage-like tape. Part of the image has been mysteriously focussed. The yellow colour signals 'danger'. This work radiates an atmosphere of threat. What is evoked is the suffering of the prisoners of war under the Japanese occupation of Birma during the Second World War. The title of this work, and the railway line, like the name Auschwitz, allude to the catastrophe and the atrocities of war in general. Wiegant was born in Indonesia and is of a generation still influenced by Dutch Colonialism. In any case, these photographic works form an important counterpoint to his paintings

"This tower was a giant standing with its back to the plight of the ants. It represented to a degree, to the correspondent, the serenity of nature amid the struggle of the individual - nature in the wind, the nature in the vision of men. She did not seem cruel to him then, or beneficent, or treacherous, or wise. But she was indifferent, flatly indifferent."

Maybe that's why Mondriaan did not like nature - maybe he found her too indifferent. (Incidentally, it is noted that he travelled by steamer to New York). Wil Wiegant, through his Dutch extraction and through his aesthetic attitude, has something in common with Mondriaan (except for his dislike of nature). There are similarities in his tendency towards a hermit-like existence, there are similarities in his use of the grid pattern and the variations on certain motifs and there are similarities in the importance of primary colours in his work amongst other things. The name 'Mondriaan' stands for a Utopian hopefulness (of cultural and social progress through art) and for the religious kernel of the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century through to the last avant-garde movements of the sixties and seventies which followed. For today's generation to which Wiegant belongs, such a Utopian view is unthinkable and no one believes in an earthly or heavenly paradise, although the longing for it has by no means abated.

Wiegant's 'boat', therefore, is also a sign of the artist's life - it stands for the development of the artist's way of thinking, the subjectivity that has to create certainty and meaning from itself.

"When (after three of the four men reached the shore alive) it came night, the white waves paced to and fro in the moonlight, and the wind brought the sound of the great sea's voice to them on the shore, and they felt that they could then be interpreters."